(picture above: First concept sketches for “Darwin Toolbox”, drawn by Oran Maguire)

The earliest sketches for what would eventually become Bento Lab were drawn in the summer of 2013. Bethan Wolfenden and I had just spent a year visiting DIYbio communities in Europe and the USA. We were excited by the spirit of interdisciplinary collaboration and the potential for synthetic biology in citizen science.

Motivation for Bento Lab came from many different directions

Together with a group of UCL students and the DIYbio group at the London Hackspace, we had run a pilot project to explore the potential and limits of synthetic biology research outside of the university. We were frustrated by the lack of equipment, and easily accessible research materials, but we also experienced that we could build ad-hoc equipment when we needed it, such as a light-bulb duct-tape shaker-incubator.

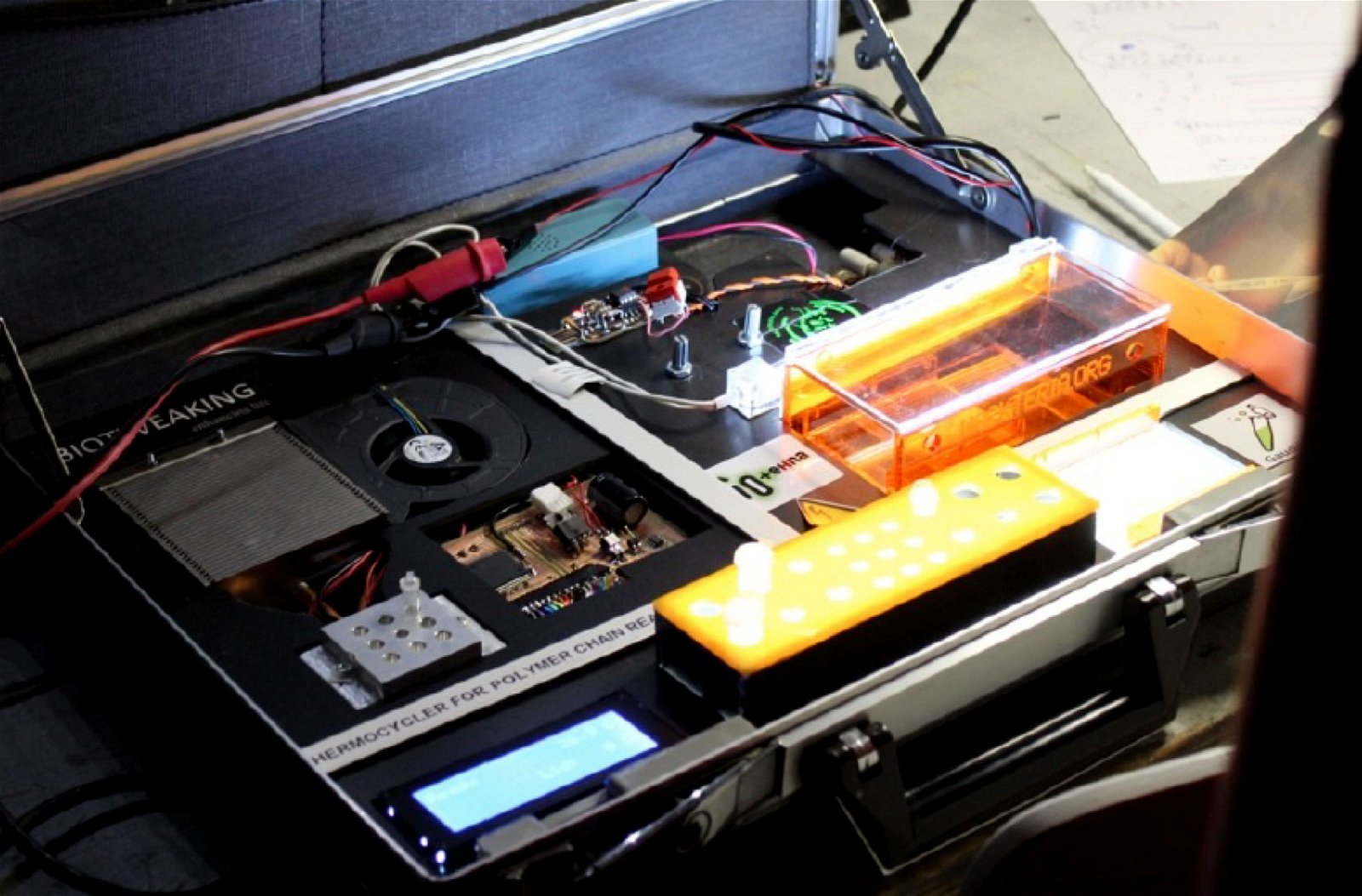

When meeting other practitioners in the DIYbio scene, we saw many different takes on self-built lab equipment, including the brief-case lab that Hackteria had designed, which was an obvious early inspiration.

iGEM Entrepreneurial Competition

While we were students, both Bethan and I were active participants in iGEM – the international genetically engineered machine competition, a do-it-together research competition for synthetic biology students. iGEM had recently launched a special track for entrepreneurial project ideas, and this seemed to us to be the perfect vehicle to develop an initial pitch for the idea.

We chose an entrepreneurship focused competition, because it was our conviction that we needed to develop Bento Lab as a functioning, sustainable company, if we wanted it to have real-world impact.

The original team for the iGEM pitch also included designer Marek Kultys, and UCL students Oliver Coles, Tom Catling and Des Schofield.

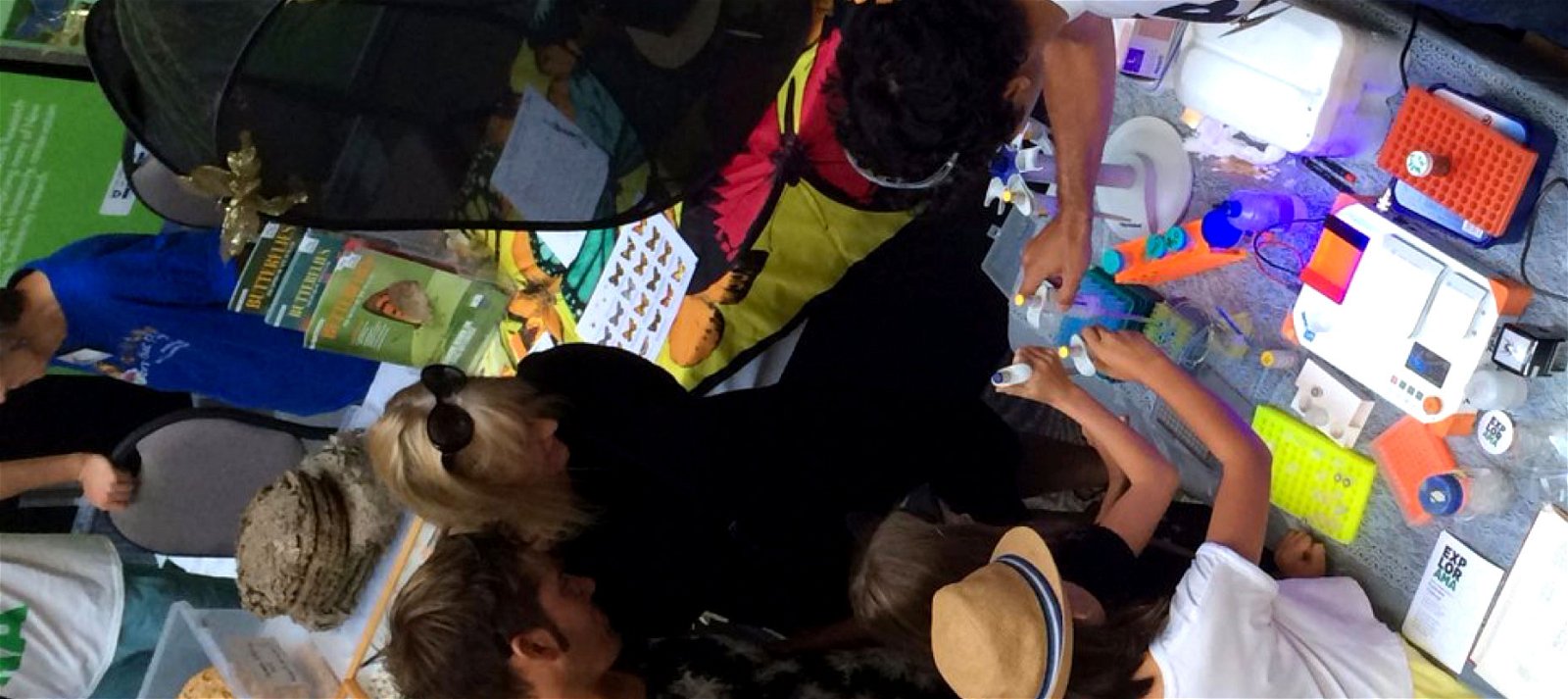

We were lucky to receive some recognition from awards, such as UCL’s Focus on the Positive, and from the Royal Academy of Engineering. This pushed us to continue to refine the concept, and use use opportunities like conferences and Maker Faires to collect ideas and feedback.

In 2015, when I spent a year in Tokyo, we pitched Bento Lab at the Slush ASIA start-up competition and to our surprise, we were placed as a finalist.

Beta Testing and Kickstarter

Up until this point, Bento Lab still remained conceptual. We had developed a number of prototypes, and we had collected lots of feedback and application ideas. Our next step was to test whether Bento Lab was not just an engaging concept, but could also be a practically useful product.

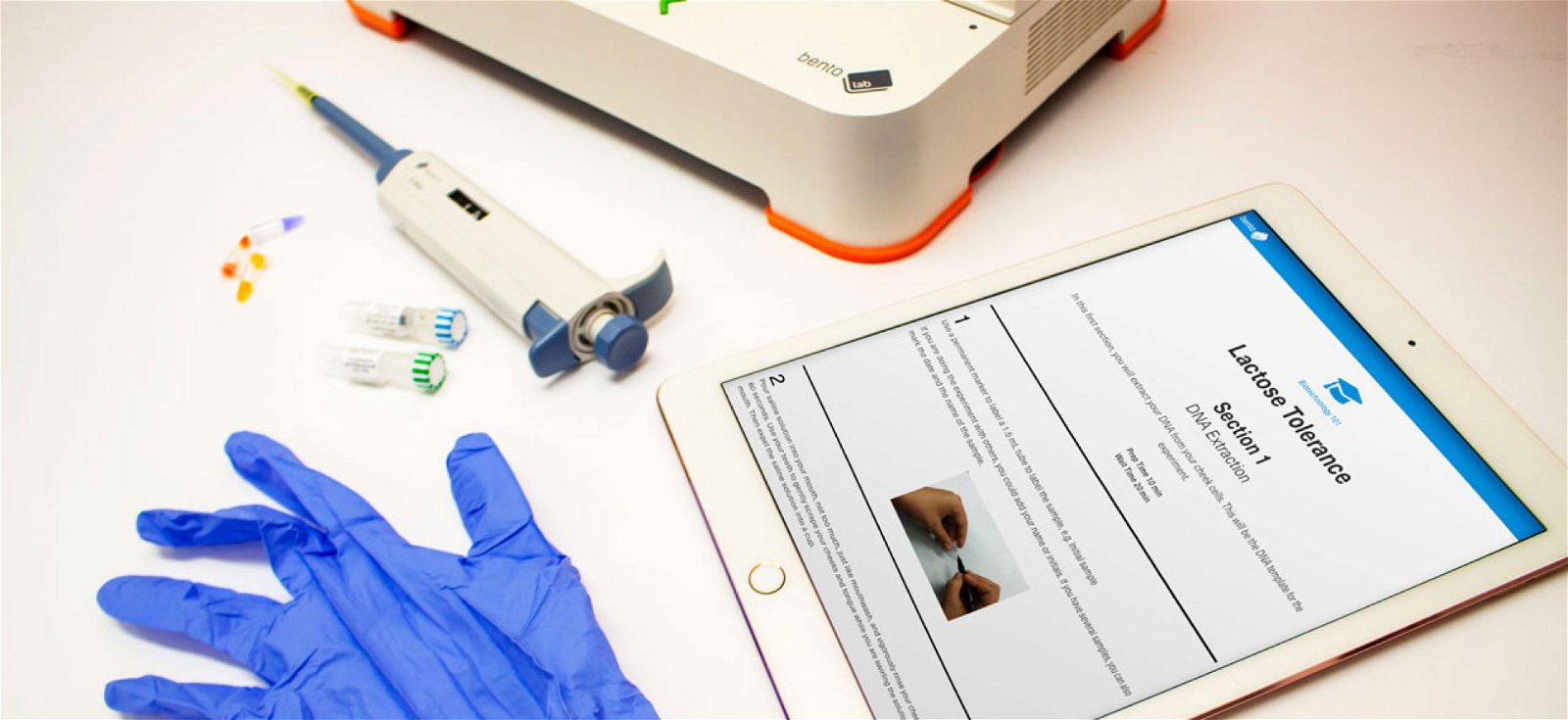

We announced a beta testing program on our website, and rented out purpose-built beta testing models to testers working in specific applications, from field research, education and outreach, and citizen science. Our beta testers pushed us forwards, and surprised us with their creativity. One of our first testers was Gianpaolo Rando, who used Bento Lab as part of his Beer DeCoded project, analysing the microbiome of craft beers. Stephane Boyer, of UNITEC in New Zealand, was the first to show off Bento Lab together with a Oxford Nanopore MinIon. The feedback from our beta testers then formed the basis for our Kickstarter campaign.

The Blog and The Future

From the start, our mission has been to bring biosciences to more people. Initially, we were focused in particular on hardware for synthetic biology, and soon we pivoted our focus to accessible molecular biology in general.

We also realised early that hardware was necessary, but not sufficient. Even more important would be easy-to-use reagents to facilitate learning and particular applications, as well as easy-to-understand knowledge resources.

To move closer towards the goal of our mission, we are convinced that we need to tell stories showcasing positive examples of widely accessible biosciences. We have experienced that Bento Lab has been an effective artefact for generating conversations and ideas for biosciences beyond the traditional lab, because its unique design radically reimagines what form a laboratory can take, and who it could be used by.

As part of our mission, we believe that we need to become more effective in sharing the stories of the people using Bento Lab in their research, their educational practice, and beyond, as well as other inspiring stories of Do-It-Yourself and Do-It-Together biosciences.

This blog is part of that effort. Please consider sharing it and help us engage more people with a positive and accessible future of biology.

Thank you!